Constellation's Vertical Roll-Up: Still Worth the Price?

Constellation Software (CNSWF) doesn't trend on Twitter. It doesn't host flashy product keynotes. But over the past two decades, it's quietly compounded shareholder capital at a pace that leaves most hot tech stocks in the dust. This is a business that wins not by chasing the next big thing, but by buying the small, boring software companies nobody else notices and turning them into cash-flow machines. In a market obsessed with growth-at-any-price, CSU has built its empire on the opposite: patience, discipline, and hundreds of micro-monopolies that almost never let go of a customer.

1. Business Model A Compounding Machine Hidden in Plain Sight

While most investors chase the next AI breakout or viral SaaS story, Constellation Software quietly compounds capital like few businesses on Earth.

There are no flashy product launches. No blitzscaling. No hype. But under the radar, CSU has built one of the world's most efficient capital allocation engines not by creating groundbreaking software, but by owning the software that quietly powers the world's most specialized workflows.

The model is deceptively simple. CSU acquires vertical market software (VMS) companies niche tools designed for specific industries like cemetery management, dental clinics, marina scheduling, or municipal tax systems. These aren't billion-dollar TAMs, and they're not meant to be. But inside their micro-verticals, CSU's companies are often the default and sometimes the only solution available. They dominate their domains with loyalty, pricing power, and astonishing customer stickiness.

What makes these businesses special isn't speed. It's resilience. Once embedded, the software becomes part of a company's operating DNA. Switching means retraining staff, migrating data, and reworking internal processes an operational headache few clients are willing to endure. As a result, CSU's software becomes the infrastructure like electricity or water silently mission-critical.

Unlike traditional roll-ups, CSU doesn't force conformity. Acquired companies retain their autonomy and operate under one of six decentralized operating groups: Volaris, Harris, Jonas, Vela, Perseus, or Topicus. Each functions as its own mini-Berkshire, complete with its own team, culture, and M&A engine.

And it works. CSU has executed hundreds of acquisitions, often for businesses generating <$10M in annual revenue. Most deals are all-cash, acquired at conservative multiples, and must clear strict IRR thresholds typically 2030%. It's a self-funding flywheel: recurring revenue fuels cash flow, which is reinvested into new acquisitions, which generate more cash and the cycle repeats.

The results speak for themselves. Since 2012, CSU has grown revenue from $891 million to over $10 billion in 2024 all without overleveraging or diluting shareholders. Share count is stable. Growth is funded with cash, not hype.

Forget the software company label. CSU is a world-class capital allocator that just happens to buy software. And the more boring it looks, the more powerful it becomes.

2. Industry and Moat Hundreds of Micro-Monopolies Quietly Printing Cash

Vertical market software (VMS) doesn't sound like the kind of battlefield where you'd find one of the world's best compounders. But that's exactly where Constellation Software thrives.

Instead of going head-to-head with enterprise giants or chasing hot SaaS trends, CSU quietly builds a decentralized empire in the long tail of software a universe of niche, high-stakes applications where few competitors exist and switching costs are enormous. This is where moats are structural, not superficial.

Across its 600+ subsidiaries, Constellation owns mission-critical software that runs everything from public transit in Scandinavia to funeral home management in North America. These aren't glamorous markets. They're ignored. But that's the edge Constellation faces almost no competition, minimal churn, and pricing power that compounds quietly in the background.

What binds these verticals together is customer lock-in.

When Constellation acquires a business, it's not buying growth. It's buying control of a system that its customers literally can't function without. Whether it's due to compliance, regulation, or deeply entrenched workflows, the software becomes the standard operating system. Replacing it means retraining staff, rewriting processes, requalifying systems and in many cases, risking noncompliance.

Most clients don't even try. That's what makes the revenue so sticky.

These aren't just sticky businesses. They're structural monopolies.

In markets this small, dominance becomes exclusivity. There isn't room for three or four competitors there's often only room for one. And since Constellation typically acquires companies with 1020 years of existing customer relationships, it inherits a trust moat that's almost impossible to replicate.

But the moat doesn't stop at the customer level. It extends all the way up the M&A funnel.

CSU is frequently the first and only call for founders looking to sell. Unlike private equity, it doesn't slash headcount, flip assets, or impose short-term KPIs. It offers something founders actually care about: long-term stewardship. That's rare. And it makes Constellation the buyer of choice in a space where relationships often matter more than bids.

This advantage feeds itself. The more companies CSU acquires, the more inbound referrals it gets. It's a flywheel few can match.

And Constellation keeps its edge by staying disciplined. No banker-led roadshows. No inflated valuations. No deal frenzy. Even as competition for software assets has intensified, Constellation continues to walk away from overpriced deals a discipline that's helped preserve its long-term IRR targets and capital efficiency.

3. Management and Incentives Mark Leonard's Capital Discipline Engine

In a world obsessed with visionary founders and quarterly soundbites, Mark Leonard stands apart.

He's not on earnings calls. He doesn't do CNBC interviews. He rarely writes shareholder letters and when he does, they read more like essays on philosophy than finance.

But behind the low profile is one of the sharpest capital allocators in public markets.

Leonard founded Constellation Software in 1995 with a simple idea: buy great little software companies, let them run independently, and reinvest every dollar of cash flow with discipline. That formula has quietly turned a C$25 million roll-up experiment into a C$100 billion powerhouse.

No hype. No empire-building. Just execution.

CSU's internal return hurdles say it all: 20% expected IRR for larger deals, 30%+ for smaller ones. If a deal doesn't meet that bar, it's out no exceptions. That means some years are quieter on the M&A front. Occasionally, the company even pays a special dividend instead of forcing subpar capital deployment.

That restraint isn't a bug. It's the design.

Constellation's model breaks from the typical command-and-control corporate structure. Acquisitions aren't absorbed into some bloated org chart. They stay independent same leadership, same brand, same P&L. No forced integrations. No rebranding. No synergy consultants.

Instead, each business is plugged into one of six decentralized operating groups: Harris, Volaris, Jonas, Vela, Perseus, and Topicus. Each group runs its own playbook setting strategy, managing its own M&A, and being held accountable for long-term return on invested capital (ROIC), not short-term earnings per share.

This is capital allocation as a system not a personality cult.

And it scales. Rather than centralizing decisions, Leonard's model multiplies independent competence. The operating group leaders many of whom have been with CSU for over a decade aren't just managers. They're capital allocators trained to think like investors.

Incentives reflect that mindset. No gimmicky stock comp or vanity metrics. Just long-term capital efficiency and real accountability.

Leonard leads by example. He takes no salary. He's never sold a single share. He owns 407,797 shares worth ~$1.4 billion making him CSU's largest individual shareholder. That's not just alignment. That's permanence.

Even when it comes to portfolio strategy, Leonard thinks like an owner. The spinouts of Topicus (focused on Europe) and Lumine (telecom) weren't done for optics. They were deliberate moves to preserve strategic focus and avoid diluting return thresholds in Constellation's core.

The result? A culture of discipline that institutional investors trust and back with size.

Akre Capital Management (Trades, Portfolio), one of the world's most respected long-term investors, has made CSU a core position. As of April 2025, Akre owned 458,500 shares worth over $1.57 billion 13.10% of its portfolio. That position speaks volumes. Even after trimming slightly this quarter, Akre is still betting on the team, the model, and the durability of CSU's playbook.

In a market full of growth-for-growth's-sake rollups, Constellation Software stands out as something rare: a company that buys small, thinks big and never forgets that capital is scarce.

This isn't just management alignment. It's institutionalized capital discipline. And it's the real engine behind CSU's long-term compounding.

Where traditional software firms chase the next big feature or sales-driven growth, CSU does something different: it bets on permanence. It owns the back-end systems that rarely get headlines but always get paid.

This isn't a moat built on brand, buzz, or blitzscaling. It's built on time, trust, and hundreds of embedded micro-monopolies each compounding quietly while the rest of the market looks the other way.

4. Financials An Engine That Converts Every Dollar Into Two

Constellation Software doesn't chase headlines and neither do its financials. But under the hood, it's one of the cleanest capital compounding stories in global markets.

There's no reliance on venture-fueled hypergrowth, and no dependence on a single product or segment. Just disciplined execution, cash-generating businesses, and one of the most capital-efficient playbooks in software history.

Let's break it down.

A Decade of Double-Digit Growth, Without the Dilution

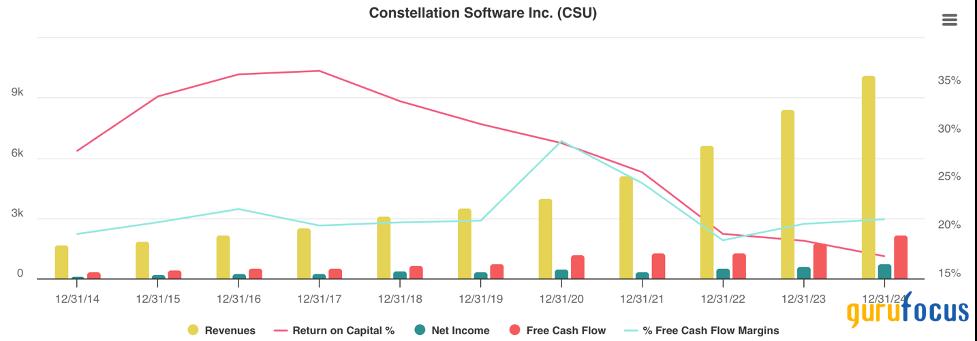

From $891 million in revenue back in 2012 to over $10 billion in 2024, CSU has delivered a ~22.3% CAGR over the last 12 years.

There's no magic trick here. Growth has come from hundreds of disciplined acquisitions, each adding recurring revenue streams and a little more operating leverage. Some years see 30 deals, others over 100 but volume is never the goal. Returns are.

And that's what sets CSU apart. While other acquirers fund growth with equity dilution or aggressive leverage, Constellation runs lean. Share count is flat. Debt is modest. Growth is internally funded.

GAAP Earnings Understate the Real Power

In 2024, CSU reported C$1 billion (~$731 million USD) in net income a solid headline. But like many acquisitive companies, GAAP earnings miss the full picture.

Why? CSU expenses the amortization of acquired intangibles a non-cash charge that significantly reduces reported profit but has no impact on actual cash flow. If you're tracking net income, you're only seeing half the story.

Follow the Cash: Free Cash Flow Tells the Real Tale

In 2024, operating cash flow hit nearly US$2.2 billion (C$3.1 billion), with free cash flow (FCF) margins topping 21%. That's not a one-off. Over the past decade, FCF has compounded at ~20.6% annually, and CSU regularly generates 23 more free cash than its reported earnings an extremely rare feat in any sector, let alone software.

But when you strip the story back to simple math, the challenge comes into sharper focus. As in the past 15 years, its average FCF multiple is around 20x. To justify a C$100+ billion (~US$74 billion) valuation on an average 20x FCF multiple, CSU might need to be generating in the ballpark of US$3.7 billion in FCF.

Historically, the company has acquired over 600 businesses, thus on average, each one adds about $3M in FCF. Getting from US$2.2 billion to US$3.7 billion using only this formula implies acquiring around 500 more similar-sized companies. That's roughly 100 deals a year a pace they've occasionally hit, but would need to sustain for at least five years straight.

The alternative is buying bigger. But bigger means a different game. Those deals come with higher price tags, fiercer competition, and a greater risk of returns slipping below CSU's historical IRR thresholds.

The market seems confident they can keep the small-deal flywheel spinning. The real question is whether that confidence is warranted and whether the opportunity set is deep enough to feed it.

And with private equity increasingly targeting the same founder-owned niches, maintaining CSU's historical IRR thresholds will require even more selectivity in the years ahead

Capital Efficiency That's Off the Charts

CSU doesn't just generate cash. It barely needs to spend any of it to maintain operations.

Capex is minimal typically under 5% of revenue and working capital needs are tightly controlled. There's no inventory. Receivables are short-dated. Credit risk is low. It's a capital-light model with high visibility and minimal fragility.

Leverage? Conservative. Net debt runs at ~1.1 EBITDA. Interest coverage is high. The company could lever up if needed but chooses not to.

ROIC: The North Star

Constellation's internal compass is return on invested capital. And it delivers.

Across hundreds of small, acquired units, CSU consistently posts ROIC in the 17.3% to 36.5% range far above software peers, private equity benchmarks, or even top-quartile compounders.

That kind of return, repeated and scaled across 20+ years, is what powers the compounding. It's also what limits downside because every dollar CSU deploys is expected to double within a few years.

A Financial Profile Built for This Market

Today's environment rewards capital discipline. With higher rates and tighter capital markets, the companies that thrive are those that can grow without constant funding.

That's Constellation to a tee.

- Flat share count

- Internally funded growth

- Low capital intensity

- High returns on capital

- Recurring, recession-resistant revenue

This isn't a business that swings for the fences. It's one that gets on base again and again and compounds with relentless consistency.

And in a market full of flashy stories and negative FCF, that's not just rare. It's gold.

5. Valuation Not Cheap, But Maybe Fair for a Rare Compounder

Constellation Software doesn't trade at a discount and that's no accident. This isn't a misunderstood business or a cyclical turnaround waiting for sentiment to shift. Investors know exactly what they're buying: a disciplined capital allocation engine, with industry-leading returns and a two-decade track record of compounding without drama. The current valuation reflects that reality.

At today's levels, CSU trades at roughly 41 forward operating earnings and about 30 forward free cash flow, which implies a free cash flow yield of around 3.3%. On paper, that's expensive especially for a business that only grows organically at low single digits. But that traditional lens misses the essence of Constellation. This isn't a company banking on margin expansion or a rerating to deliver returns. It's a machine that compounds cash at high returns, redeploys it into sticky, cash-generating acquisitions, and repeats over and over.

The more relevant question isn't Is it cheap? but What assumptions are baked into the price? A reasonable base case assumes that, as Constellation matures, free cash flow compounds at a slower but still strong pace of 15% annually. If that trajectory holds for a decade, and the company exits still trading at roughly 30 FCF, long-term shareholders can expect IRRs that mirror that growth rate. No heroics. No multiple expansion needed. Just continued execution.

Of course, not every scenario looks this clean. If growth decelerates more sharply say, down to 78% annually and the market trims the multiple closer to 20, expected returns fall into the low-single-digit range. Not disastrous, but a long way from the premium price tag being justified.

So where's the margin of safety? It's not in the multiple. And it's not in the headline growth rate. It's in the quality of the business. CSU's cash flows are recurring, its moat is structural, its culture is disciplined, and its capital allocation is tested across cycles. That embedded quality isn't always visible in the valuation tables but it matters. Especially in a market where plenty of lower-quality software companies are trading at similar or even higher multiples with far less to show for it.

If you're paying 30 FCF, it should be for a company that's earned the right to reinvest every dollar with confidence and has done so, year after year, without the need for narrative or leverage. Constellation fits that profile. It's not cheap. But it's clear-eyed, battle-tested, and built to last.

As Buffett put it: It's far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price. CSU is exactly that a wonderful business. And at these levels, the price looks fair enough for those playing the long game.

6. Risks and Red Flags Not Immune, Just Resilient

Constellation Software might be one of the best-run businesses in public markets but no model, no matter how disciplined, is bulletproof. CSU has built its moat through decades of careful execution, but that doesn't mean it's immune from risk. The good news for long-term investors: most of these risks are visible, familiar, and manageable. The bad news: they're very real, and they matter.

The most important risk is reinvestment capacity. CSU's entire model hinges on its ability to deploy large amounts of free cash flow at high returns. As the company grows, that gets harder. The bigger the base, the harder it is to find enough small, high-IRR targets to keep compounding at the pace investors have come to expect. With the gap between today's FCF and the level needed to justify its valuation, the sourcing engine must run at near-peak efficiency for years to come.

History offers a cautionary parallel. From 2005 to 2020, Danaher ran a strikingly similar playbook under Larry Culp: hundreds of disciplined small-company acquisitions, each feeding a compounding flywheel. Eventually, the pipeline of bite-sized targets thinned. Growth shifted from exponential to linear. The board pushed for larger acquisitions to keep the game going, but returns moderated. Culp a CEO as methodical and philosophically minded as Mark Leonard left, in part because he saw the limits of the small-deal strategy.

That raises two big questions for CSU: How long will Leonard remain at the helm, and what's his view on the depth of the remaining target pool? He hasn't said publicly how many high-quality small companies are still worth buying or what CSU will do if the well starts to run dry.

Succession is another issue investors can't ignore. Mark Leonard is still deeply involved at the strategic level, but the day-to-day is now largely driven by the operating group heads. The company has been built to outlast him with decentralized leadership, embedded capital discipline, and an internal bench that knows the model. Still, Leonard is more than a founder. He's the intellectual architect behind the culture, the discipline, and the long-term orientation that define Constellation. If leadership drifts from that ethos chasing bigger deals, loosening IRR targets, or prioritizing optics over substance the compounding engine could slow.

Operationally, the risk is more subtle. Some CSU businesses still run on aging, on-premise software. For most customers, that's fine the software is stable and the functionality is what matters. But in certain verticals, cloud-native challengers are emerging. If CSU underinvests in product upgrades or fails to buy these challengers fast enough, it could face higher attrition or margin pressure. So far, the company has used selective reinvestment and bolt-on M&A to stay ahead but complacency here could create cracks in the moat.

And then there's valuation risk. At ~30 forward FCF, CSU is priced for continued execution. That's fine until it's not. If organic growth slows, or if deal volume falters, or if capital deployment becomes less efficient, the market could quickly reprice the business. In a compounding story like this, even a small signal of deteriorating ROIC can reset expectations sharply. While the core cash flows are stable, the stock is still exposed to shifts in sentiment tied to the quality of reinvestment not just headline results.

None of these risks break the thesis on their own. But they're reminders that Constellation's engine only works when it stays disciplined in deal sourcing, in capital allocation, and in culture. Fortunately, those traits have defined CSU from the start. And for now, the evidence suggests they remain intact.

7. Final Investment Thesis

Constellation Software isn't built for headlines. It's built for endurance. The model is simple but lethal: buy essential vertical market software, keep it independent, and redeploy cash into more of the same with discipline. The challenge is scale. As CSU grows, the pool of small, high-IRR deals shrinks, and private equity is circling the same niches. Hitting the US$3.7 in free cash flow implied by today's valuation will take peak-level sourcing for years.

But few companies are better wired for that challenge. CSU's culture is capital discipline, not growth-at-any-price. Its decentralized model has produced investor-minded operators who can adapt moving upmarket, bolting on to existing platforms, or expanding into under-penetrated geographies without breaking the model. At ~30 forward FCF, it's not cheap. But it's the kind of business where time, not multiple expansion, drives returns. In the base case, high-single-digit to low-double-digit compounding is realistic. In the downside, growth slows but capital is preserved. Buffett once said, Time is the friend of the wonderful business. And CSU still fits that description.